Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association

Cree Hatchery and Trust Visit 4th Feb. 2024Visit Report |

Colin Liddell, LLAIA Chairman

Email address [chairman@lochlomondangling.com]

Website: [www.lochlomonangling.com]

CONTENTS

Introduction

- Executive Summary

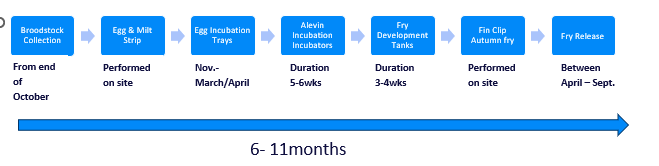

- The Hatchery Process Overview

- Success Indicators

- Funding and Support

- Summary

- Appendix 1 Galloway Fisheries Trust: Management of Fisheries

INTRODUCTION

The following report is a summary of a visit organised by the Loch Lomond Angling Association to the River Cree Hatchery and Trust in Ayrshire.

The visit was kindly hosted by Murdo Crosbie – River Cree Hatchery & Trust Manager and attended by:

Jamie Graham – Montrose Estates

David McClymont Vice Chairman LLAIA

James Scanlon – VOLDAC LLAIA Representative

Colin Liddell – Chairman LLAIA

Dr Nick Beevers – Senior Biologist LLFT

Fergus MacFarlane – Biologist LLFT

Jay Malpas – Biologist LLFT

EXCECUTIVE SUMMARY

| Objective of visit

The purpose of this visit was to better understand the work that has been undertaken by the Cree Hatchery & Trust in relation to their approach, processes and successes in supplementing local Atlantic Salmon numbers within their catchment. Established in 2010 by a group of conscientious members of the local angling club the River Cree Hatchery and Trust is a charity-based organisation relying almost entirely upon grants and donations. The Cree Hatchery and Trust has only one salaried employee – hatchery manager Murdo Crosbie. The Trust has been and is supported by the local DSFB. The Cree Hatchery and Trust was established with the main aims for establishing a stocking management plan and capability due to the following threats: · Poor Water Quality (Ph levels 3.7-4.0 regularly measured) · Degraded habitat · Increasing large spate events resulting in Redd washout · Siltation · Predation The overall aims of the Cree Hatchery and Trust are as follows: · Stock out areas of the catchment with low or no populations of wild salmon juveniles · Improve degraded habitat · Predation control · Education – local community engagement and in particular you people In terms of results then I believe that Hatchery Manager Murdo Crosbie would agree that even with this investment and effort the Cree fishery rather than seeing a rapid increase in salmon population is in fact ‘holding steady’ based upon the last ten or so years of rod catch returns compared to neighbouring rivers and catchements. |

What is notable however is the significant percentage of current rod catches and electro fishing caught fish that are fin clipped and therefore hatchery fish. When you consider that only 20% of the total hatchery fry released are fin clipped autumn fry then the proportion of the current salmon population that are hatchery fish within the catchment is likely to be very high indeed. It is therefore difficult to imagine what the natural population remaining within the catchment would therefore have been without this intervention.

SUCCESS INDICATORS

From this visit and the information supplied then some examples of success concerning the hatchery yields were provided. It is understood that rod catch returns are a very crude measure. The following shows the percentage of fin clipped fish within recorded rod catches. It is understood that not all catches were reported and not all fish that were caught were recognised as hatchery fish.

- 2020 – 18%

- 2021 – 19.4%

- 2022 – 11.1% (hi spate conditions impacted electro results)

- 2023 – 21.2%

In 2022 electro-fishing surveys identified 10% of adult fish were fin clipped adults whilst capturing brood stock out of 60 fish removed.

In 2023 electro-fishing surveys identified 19% of adult fish were fin clipped adults whilst capturing brood stock removed.

With the exception of 2018 and 2019 (drought conditions) and 2021 (the Covid year) it was highlighted that reported rod catches across the catchment have slowly but steadily either held up or increased since 2010 when the hatchery was launched. With the exception of the River Luce, these results are in contrast to most of the surrounding rivers like the Annan, Girvan etc.

What was noted was the very positive engagement and participation of local schools and other groups visiting the hatchery. This provides awareness and education to the local community in relation to the natural environment, the salmon lifecycle, threats to salmon and climate emergency. Many of these activities are hands-on involvement in fry release and fishing introduction to youngsters.

Whilst these results are encouraging, they are based upon a very small sample. It would have been helpful if more quantitative studies and data was available.

FUNDING AND SUPPORT

The hatchery was originally established in 2010 with the hatchery site being gifted to the Trust by a local land owner. NSAA and local council grants provided some financial support. The largest start-up cost was related to the building itself at a build cost of £37k at that time with much of the remaining materials and construction work being donated by local companies and volunteers.

An estimate of the actual cost without donations of materials and labour would be well over £80k. The building itself measures 28 feet by 68 feet and it is now recognised that a larger building would have been beneficial.

In terms of the annual operating expense of £35k then the majority of the Hatchery operations is funded via grants and charitable donations. The Cree Hatchery and Trust raise funds annually from grants and by encouraging local businesses to fund one or more tanks or by conducting raffles with prizes such as holiday accommodation being donated by individual supporters.

A key part of this operating cost is the only full-time employee of the Cree Hatchery and Trust is the hatchery manager Murdo Crosbie.

SUMMARY

The visit to the Cree Hatchery and Trust was very informative and interesting. As Murdo himself would state, the results of the stocking programme and efforts have not resulted in a large spike in the population of salmon within the catchment in terms of rod catch returns.

It would appear however that the investment and work here has ‘stabilised’ the wild salmon population that most likely would have otherwise suffered a significant decline. It is evident that the hatchery in itself is not the silver bullet or only mitigation needed in this case and the Cree Hatchery and Trust together with other agencies are therefore currently also addressing habitat and water quality issues as well as other threats as part of an overall management plan for the fishery. From an improvement viewpoint then work continues to address each of the other threats.

The Galloway Fisheries Trust in their support of the Cree Hatchery and Trust have outlines the importance and need for a holistic ‘Fisheries Management Plan’ and where appropriate the use of hatcheries stressing the importance of a code of practice. (see Appendix 1). The use of systematic electrofishing surveys continues to be a key element of the management plan in order to provide measurement and reporting as to the health and improvement of fish populations overall.

On behalf of the association and the trust I would like to extend our thanks to The Cree Hatchery and Trust and, in particular to Hatchery Manager Murdo Crosbie for so freely and willingly giving his time and for sharing his experience and knowledge with us.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1. |

Galloway Fisheries Trust: Management of Fisheries

| After working across the region’s waters for many years, GFT holds a large amount of data from each catchment. The use of Fisheries Management Plans (FMPs) is a useful way to collate this data and produce a meaningful future management strategy for a fishery or river system.

The overall aim of a Fishery Management Plan is to produce a long term management strategy, incorporating current fishery issues and management. For a river catchment this would include the river, tributaries and still waters. Plans may also include aims and objectives, a description of the fishery including an assessment of current stocks, apparent limiting factors within the fishery and a monitoring plan and review process. A vital element within the plan is the collection of basic information about the catchment or sub catchment, including relevant historical and recent data relating to the catchment. In this way any gaps in knowledge of the system will be identified. It is essential to ensure that FMPs are working documents that can be used by stakeholders, agencies and other interested parties. GFT has produced FMPs over the years but with various success. Many lessons have been learned. In 2023, Fisheries Management Scotland, Crown Estates and Marine Scotland started an initiative to support the production of evidence-based Fisheries Management Plans for Trusts / DSFBs to assist in the management of salmon and seatrout in each District. These on-line plans are presented as story maps through ArcGIS. The completed plans should be publicly available at some point in 2023. Are hatcheries the answer? |

It is known that hatcheries can actually contribute to the decline of wild fish, particularly when fish have been introduced from different catchments. Hatchery fish have also been known to out-compete wild stock, lower the fitness of potential offspring when crossed with wild stock and the progeny have even failed to survive when stocked into the wrong

| places. Much of this has been highlighted through genetic studies, where fish of hatchery origin may fail to ascend obstacles such as waterfalls as a result of the wrong ‘genetic make-up’.

Hatchery programmes do not directly increase rod catches as hatchery produced offspring will not produce significantly greater return rates than if the adult fish were allowed to spawn naturally. In fact, studies have shown that survival rates may be severely diminished, particularly smolt survival at sea. In 2011, RAFTS and the Spey District Salmon Fishery Board published some interesting results of a detailed genetic-based study that showed that from annual stocking of well over 1,000,000 eyed ova and fry, this stocking only produced 50 salmon to the anglers out of a total of over 8000 caught each year. It also has to be assumed that all the broodstock collected out of the river would naturally have produced many fish if they had been allowed to spawn naturally. Hatcheries can, however, be a useful tool in some types of fisheries management. In situations where the natural population has become critically low, man may step in to prevent in-breeding within the remaining population or re-establish viable populations in areas where populations have become extinct or very low. This is the basis of all of the stocking which GFT now undertakes. We stock watercourses with suitable habitat where acidification in the past has devastated the natural fish population through poor egg survival but where water quality has now improved to a level that introduced fish can survival. GFT has developed a code of best practice to counteract problems associated with local hatchery programmes. This considers issues such as biosecurity, genetics, stocking with native stock and the stocking at different stages of development (e.g. eyed ova versus fry). Broodstock fish are collected each winter prior to spawning using a range of methods including electrofishing, rod and line, netting and fish traps. Broodstock are separated into catchment and sub-catchment categories so that their progeny retain their natal genetic integrity and they are stocked back into their natal sub-catchment. |

Most stocking programmes across Scotland now follow the same recognised best practice as GFT. This has resulted in most hatcheries reducing their output or even closing down. Locally GFT provides guidance regarding stocking locations and best practice to the Cree DSFB and we run a hatchery on the Bladnoch on behalf of the Bladnoch DSFB. Hatchery programmes require a Brood Stock Collection License from Marine Scotland where there is a requirement to show the proposed stocking programme follows their best practice protocol.

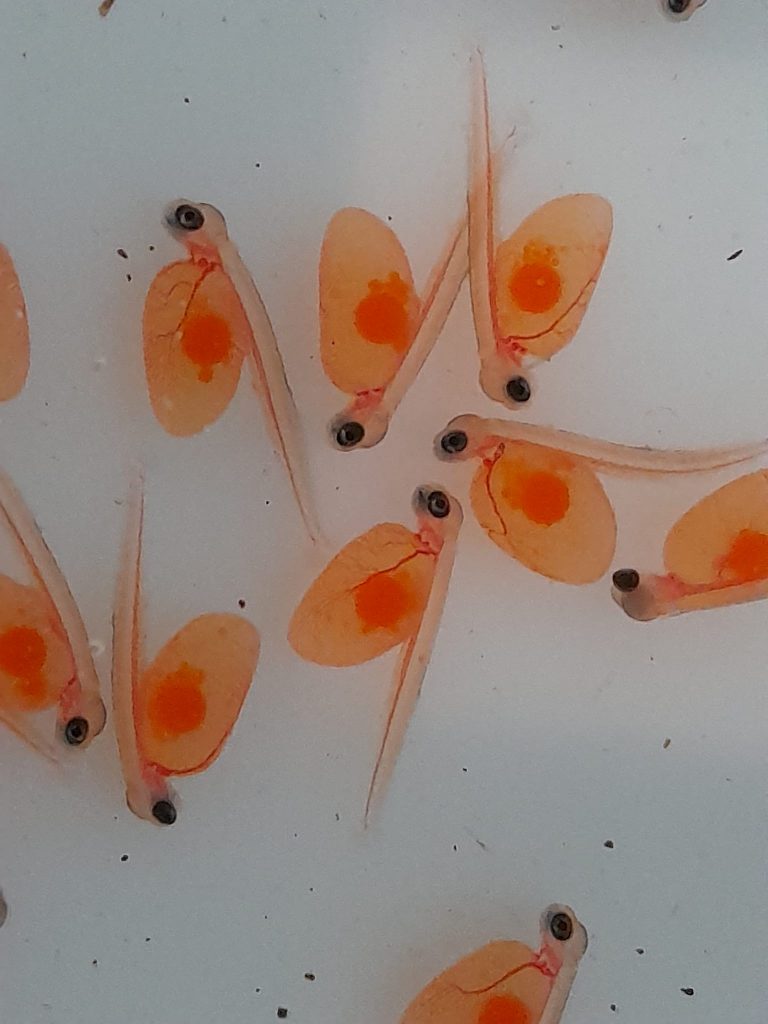

The speed at which these Alevin develop into fry is dependent upon natural air and water temperatures. Once fully developed the fry exit the nursery tank by swimming towards the light of the transpare

The speed at which these Alevin develop into fry is dependent upon natural air and water temperatures. Once fully developed the fry exit the nursery tank by swimming towards the light of the transpare